I mentioned last week that we were off to the Turner and Constable exhibition this week but what I hadn’t noticed was that it starts in November, one for later in the year then! So, after the opulence of Leighton House last week, this week, we’re off to a quite different kind of small museum. The Foundling Museum tells the history of the Foundling Hospital and of those who grew up in care. The founder, Thomas Coram, established a charitable hospital to provide shelter and education for children under Royal Charter in 1739, after several years of campaigning. The hospital provided care uninterrupted right up to 1954 and the charity, now know as Coram, continues with it’s work for children to this day.

Where last week I could feel the traces of a comfortable life of art, collecting and travel, this week, there are reflections on a different part of life. When founded, London, while heading on a trajectory of trade and exploration that would lead to wealth and the fruits of an Empire for some, for many, it was a life of poverty and a hand-to-mouth existence that often couldn’t stretch to another one to feed. The museum tells us that around a thousand children a year were abandoned to the streets of London.

It was in these circumstances that the hospital opened and it’s really quite emotional to see how the hospital was run, how children were admitted and the kind of life they had there. There is much to touch us here as you cannot help but imagine the desperation mothers must have gone through to leave their children at the hospital. This image, A Mother depositing her child at the Foundling Hospital in Paris, by Henry Nelson O’Neil, captures that desperation as a woman places her baby on a ledge that leads to a hatch and reaches for the bell to summon someone to take the child away.

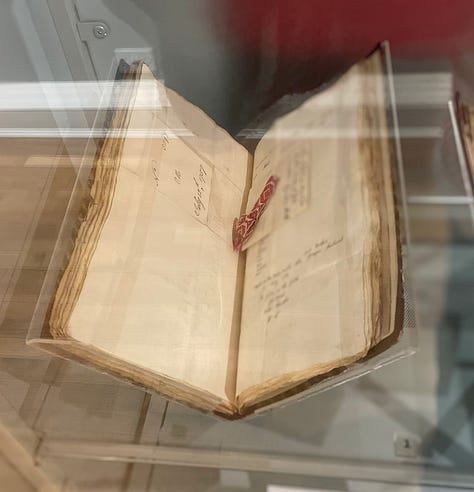

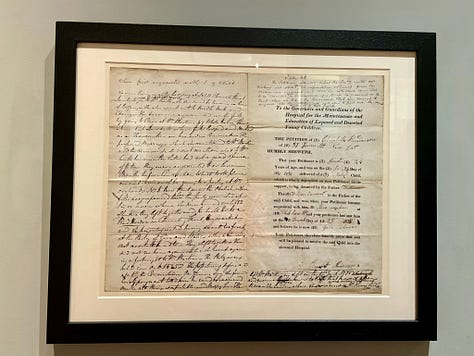

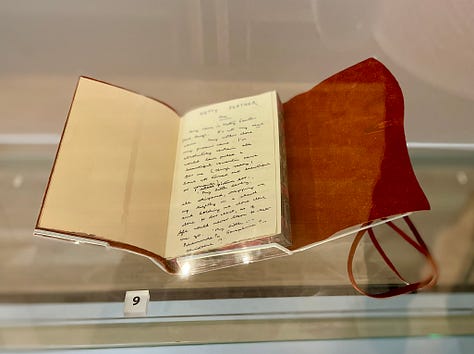

The system at the Foundling Hospital was different but I imagine no less harrowing, one aspect the museum really brings out is how the children were documented on arrival and given new names and surnames. Some mothers left a token that could be used to identify the child at a later point and these were kept with the admission details. Many of these tokens are now on display, it’s so moving, although there’s the distance of time, you can sense that attempt to tell the child there was no choice and to somehow give them some part of their mum to hang onto.

One particular aspect of the charity, right from it’s founding days, is its long history of association with artists in its charitable activities. Artists of the period, such as Hogarth and Handel were early supporters and the association to the artistic community continues to this day. There have been numerous collaborations with contemporary artists that work to bring out the many different stories of the hospital’s history, I remember seeing an exhibition by Tracey Emin which was very powerful, her legacy can be seen in a little metal mitten stuck on the railings outside the museum, if that doesn’t say child, I don’t know what does.

…if that doesn’t say child, I don’t know what does…

So, it was with interest that I thought I’d go along to the current exhibition, Self-Made: Reshaping Identities, the theme of the exhibition is self-identity and the way it shifts within us all. The exhibition features four ceramicists each bringing a different interpretation to the collection through clay.

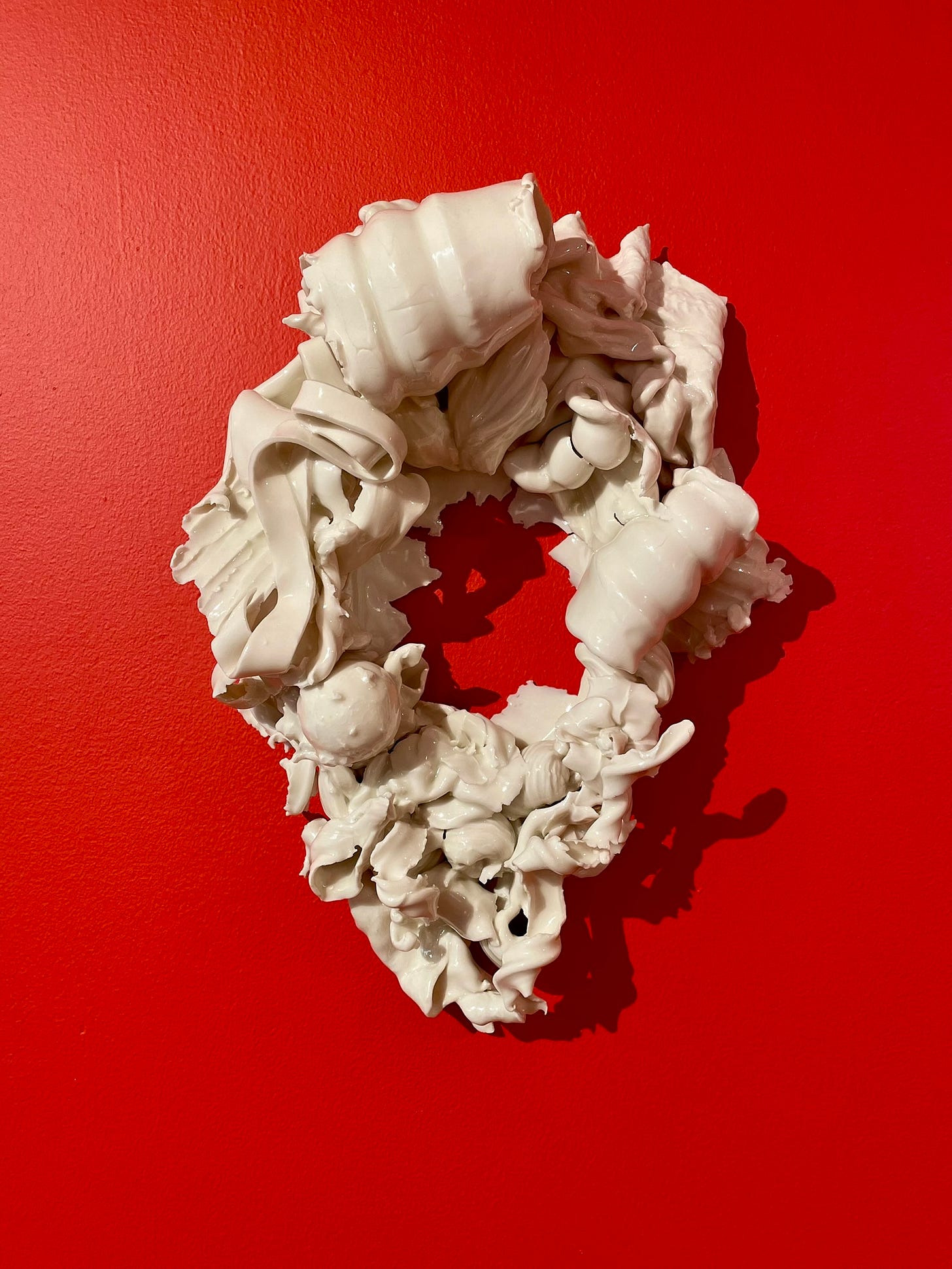

Rachel Kneebone’s works in Through a glass, (I-V), 2023, are made in fine white porcelain. The labelling tells us that they are intentionally imperfect, and a close up look reveals that they indeed are not the kind of stylised perfection you’d expect from a Capodimonte statuette but have a completely different message for the viewer. Looking at the first piece in the series of five, you get that sense of foliage and scrolls you’d normally see in fine china but here they’re disfigured, there are raggedy edges and misshapen flowers and fruits and thick undeveloped ribbons of clay. In relation to the museum it’s much as life itself, revealing it to be far more complex and chaotic than a polished perfection would have you believe. I was struck by the heart shape on a red background, it brings to mind the Sacred Heart in Catholic churches, its symbolism is often reproduced in tokens there too. There’s something here about overall love despite a confused and imperfect world.

In a series of earthenware plates, Family Romance, Matt Smith explores the nature of sexual identity, the plates commemorate relationships that pushed against the accepted norms of society. Smith makes the point that by being repressed by society at the time, the notion of a queer history was obliterated, he seeks to redress this through his ceramics. The plates remind me of the kinds of platters that were proudly displayed on dressers, here the narrative is the lives of well known couples of the 18th and 19th century. He introduces gay, lesbian and transgender couples such as Radclyffe & Una, a lesbian couple, artists, a sculptor and a poet, revealing their long overlooked histories. It speaks to us about the importance of identity and being able to acknowledge who you are.

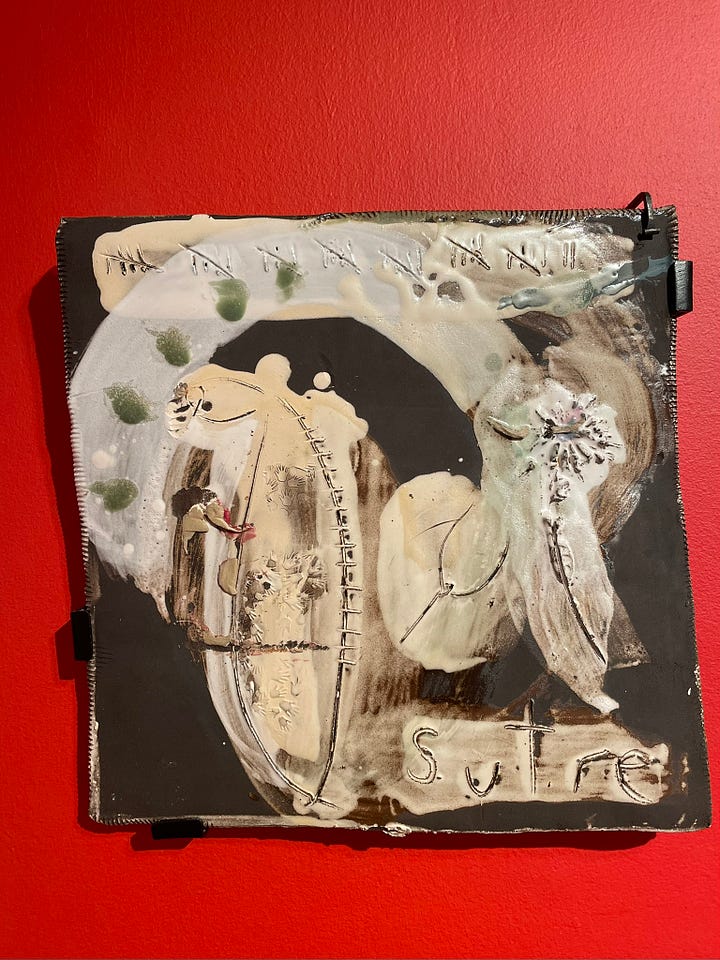

Phoebe Collings James engaged directly with objects from the museum in her works, the tile, Sutre is very emotional. The idea of stitching back together to become whole again suggests an attempt to deal with loss. We see crossed out numbers marking time and sewn stitches around tiny handprints. Does this reflect on the sewn items in the token collection? This was a period of hand sewing, long before machines, the edges of the tile also have a stitching quality, as in Kneebone’s ceramic heart, is this a picture of overall love and protection?

The last ceramicist, Renee So, looks towards ancient representations of women, often around fertility and based on the female body as an object of production. The Unknown Venus statuettes in terracotta and black stoneware pull no punches, they both point towards the origin of birth, rounded, generous bodies give that sense of softness associated with motherhood. I have to also mention Mom Jeans II, 2024, although the labelling says the piece was inspired by the rebellious ‘Sans Culottes’ of the period, all I can see is exactly the title, mum jeans, that indispensable piece of clothing that makes a mum. In no different way to the Venus fertility statuettes of old, it carries the well rounded softness that offers protection, warmth and love.

This a great small exhibition that resonates with the museum and its collection. The thing that struck me, above all, in a sea of difficult ideas to process, was the loss of identity the children had to endure, not only did they have to deal with the idea of being abandoned but to have all of their history obliterated as well, who were they then? The exhibition picks up on the notion of the loss of identity and having it repressed, however, not all is lost, the idea of an overarching, if imperfect, love and a hope for healing also comes through.

Hope you enjoyed the read, please feel free to comment with your thoughts below. Next week, the Lost Gardens of London at the Garden Museum!

Rita Fennell

Gallery Tart!